ABOUT GEORGE CATLIN

GEORGE CATLIN

(1796-1872)

“ … nothing short of the loss of my life shall prevent me from visiting (the Indians’) country and becoming their historian.”

In 1830, armed with nothing but a fist full of paintbrushes, George Catlin set out from Philadelphia to do what no man had done before—depict the Indians of the “wilds of the Far West.” Motivated by the fear of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, as well as by a briskly expanding civilization, Catlin vowed to lend a hand to “a dying nation, who have no historians and biographers of their own … thus snatching from approaching oblivion what could be saved for the benefit of posterity … perpetuating it as a just monument to the memory of a truly lofty and noble race.”

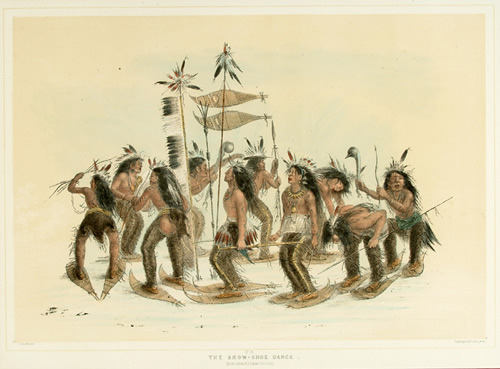

Catlin spent eight years visiting more than 45 tribes, where he participated in buffalo hunts and observed Indian ceremonies, games, dances and rituals. He emerged with 520 oil portraits and paintings of “probably the most truthful” view of scenes in Indian life ever presented to the public, portraying “man in the simplicity and loftiness of his nature, unrestrained by the disguise of art.”

Catlin’s work has been particularly noted for the “roughness and energy” of its subject matter, which left an impression not only on America, but also on Europe. Britain’s The Times wrote, “The puny process of the fox chase sinks into insignificance when compared with … the grappling of a bear or the butting of a bison.” Perhaps most importantly, Catlin introduced the work to previously un-depicted tribes, such as the Blackfoot, Crow, Plains Cree and Yanktonai Sioux Indians.

Though many of his depicted tribes are now extinct and all of the noble chiefs and brave warriors whose portraits he painted have long since died, Catlin ensured that their memory would live on through his art. In his own words, “The history and customs of such a people, preserved by pictorial illustrations, are themes worthy of a lifetime of one man.”